Well, it's happened again: A rare film I had to beg, borrow and steal to secure a copy of has now, once again, been released by a major distributor. This always fills me with conflicting feelings: pissed off that I had to work so hard for something now widely available, yet gratified that others will have no problem enjoying this fine film.

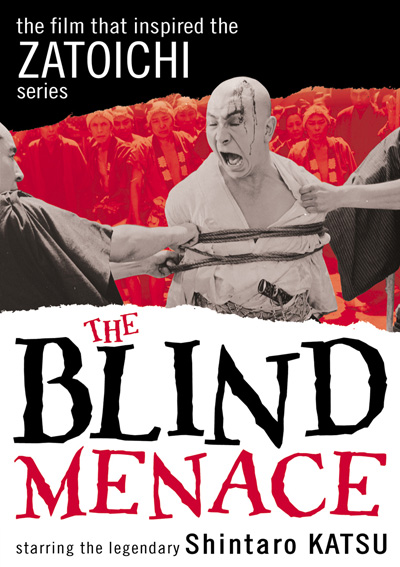

Well, it's happened again: A rare film I had to beg, borrow and steal to secure a copy of has now, once again, been released by a major distributor. This always fills me with conflicting feelings: pissed off that I had to work so hard for something now widely available, yet gratified that others will have no problem enjoying this fine film.Such a film is Shiranui Kengyo (1960), available now from AnimEigo as The Blind Menace. I wrote a review of this film in my book Warring Clans, Flashing Blades, from which I will now lazily quote (what, I gotta come up with original blog content for you? Buy the damn book, already!). The central character is a man named Shichinosuke, "a sinister, scheming blind masseur played with dark exuberance by the incomparable Shintaro Katsu. Shiranui Kengyo was the first film to showcase Katsu's unique blind man act (somewhat more exaggerated here), but this anma is the polar opposite of the actor's most celebrated sightless characterization, Zatoichi. Shichinosuke, rather than wandering from town to town, gambling, giving massages and protecting the innocent, is more inclined towards thievery, rape, extortion and murder, all employed in the service of his ruthless rise to the top."

Elsewhere I write, "Released in 1960, the film was an instant hit, elevating Katsu to full-fledged movie star. The film's success rested largely on Katsu's brilliant performance as a vile, Richard III-like villain. Like Richard, Shichinosuke's handicap fuels his rage and ambition to rise in a world where the deck is stacked against him, relishing the liberties his treachery allows him with those in the sighted world, particularly the ladies."

Elsewhere I write, "Released in 1960, the film was an instant hit, elevating Katsu to full-fledged movie star. The film's success rested largely on Katsu's brilliant performance as a vile, Richard III-like villain. Like Richard, Shichinosuke's handicap fuels his rage and ambition to rise in a world where the deck is stacked against him, relishing the liberties his treachery allows him with those in the sighted world, particularly the ladies."Then, toward the end of the review, I say: "Simply put, if you're a Shintaro Katsu fan, you have to see Shiranui Kengyo ... it's one of those holy grail pictures, not necessarily a samurai film proper, but nevertheless essential to aficionados of the genre." (Say, this guy's good!)

If I were you, while you're on Amazon buying a copy of The Blind Menace, I'd also pick up a copy of Warring Clans, Flashing Blades. Then, when that stuff arrives, go get a six-pack, kick off your shoes and get ready for a good ol' Japanese film nerd-out time. You're welcome.

(The Blind Menace streets June 15th, 2010.)